The Honour, the Struggle, and the Changing Face of Caregiving in Black Diaspora Communities

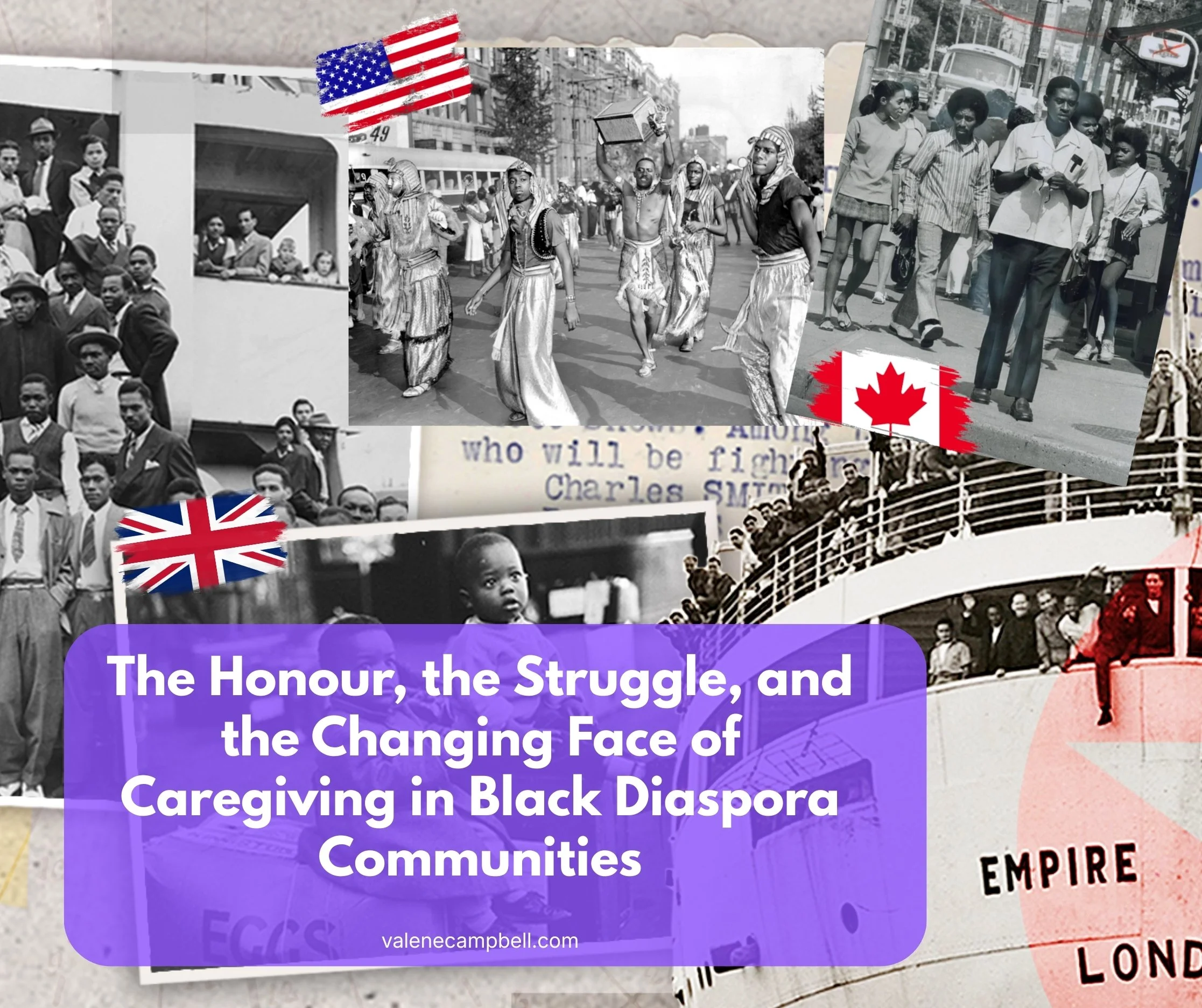

There is no greater honour than caring for the parents who raised you, who sacrificed everything so you could have more. Whether you are the descendant of those who arrived on the Empire Windrush in 1948, part of the wave of Caribbean women who came through Canada's West Indian Domestic Scheme in the 1960s, an American whose grandparents were part of the Great Migration, or the child of Nigerian, Ghanaian, or Kenyan parents who came seeking education and opportunity, this truth remains constant. In Black communities across the diaspora, caregiving is not merely a duty. It is love made visible, respect embodied, tradition carried forward.

It is the adult daughter who leaves work early to take her mother to dialysis. The son who moves his father into the spare bedroom. The family that gathers on Sunday not just to eat, but to ensure Grandma has taken her medications and that Daddy's blood pressure is being monitored. This is sacred work. This is who we are.

Yet beneath this honour lies a truth that many of us are only now beginning to speak aloud: we are carrying a burden that our parents never had to bear, navigating a caregiving reality shaped by migration, cultural dislocation, and systems that were never built with us in mind. And increasingly, we are facing an impossible choice—one that fills us with guilt even as we understand its necessity: the decision to seek professional care for our loved ones.

They Came to Build: Understanding Our Parents' Migration

To understand what being a caregiver encompasses within our community, we must first understand why our parents are here and what they came to do.

The Windrush Generation and the Building of Britain's NHS

For Caribbean families in the UK, the story often begins with the Windrush era. On June 22, 1948, the Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury with 492 Caribbean passengers, mostly from Jamaica, with others from Trinidad, Barbados, and across the islands. This became the symbolic beginning of mass migration from the Caribbean to Britain, though it was neither the first nor the only ship. The SS Ormonde had arrived in Liverpool in March 1947 with 241 Caribbean passengers. Between 1948 and 1973, nearly half a million Caribbean people would cross the Atlantic in response to Britain's call for help.

Why did Britain need them? The devastation of World War II had left the country desperate for workers to rebuild bombed cities, staff hospitals, keep buses and trains running, and operate factories. The 1948 British Nationality Act made all people from British colonies 'Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies,' granting them the legal right to live and work in Britain. For Caribbean people facing high unemployment at home, in Jamaica, unemployment was severe; in Barbados, economic prospects were bleak, and migration represented opportunity. Many who came were former servicemen who had fought for Britain during the war. They thought of Britain as the 'Mother Country.' They were British subjects coming home.

What they found was not welcome, but work that white Britons would not do. By 1948, the newly created National Health Service had 54,000 nursing vacancies. Caribbean women were actively recruited to fill these gaps. By 1965, there were between 3,000 and 5,000 Jamaican nurses working in British hospitals alone, many concentrated in London and the Midlands. By 1977, 12% of all student nurses and midwives in Britain had been recruited from overseas, with 66% of those from the Caribbean. They worked night shifts. They staffed geriatric and psychiatric wards, often considered the least prestigious specialties. They earned less than their white colleagues. They took positions in auxiliary and domestic services as cleaners, porters and canteen workers.

They also faced brutal racism. Despite having built Britain's infrastructure and staffed its essential services, the Windrush generation was subjected to discrimination in housing, employment, and daily life. 'No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish' signs hung in windows. The 1958 Notting Hill race riots saw Caribbean people attacked in the streets and their homes vandalized. Yet they persisted, working jobs that broke their bodies so their children could have education and opportunity.

Canada's Domestic Scheme and the Path to Citizenship

In Canada, the story took a different but parallel path. Before the 1960s, Canada's immigration policy was explicitly racist, heavily favouring white Europeans and restricting the entry of 'coloured or partly coloured persons.' But as Canadian women increasingly took jobs outside the home, demand for domestic workers soared. Unable to recruit sufficient numbers from Europe, Canada reluctantly looked to the Caribbean.

Beginning in 1955, the West Indian Domestic Scheme brought approximately 3,000 Caribbean women—primarily from Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, British Guiana, and St. Vincent—to work as domestic workers, nannies, and household helpers. The scheme had strict requirements: women must be single, aged 18 to 35, possess at least an eighth-grade education, and pass medical examinations conducted by Canadian immigration officials. They were brought on one-year contracts, living in their employers' homes.

The conditions were often exploitative. These women worked long hours for lower pay than white domestic workers. Many endured isolation, loneliness, and vulnerability to abuse—economic, emotional, and sometimes sexual. They lived alone in unfamiliar houses, separated from the communities they might have formed. The threat of deportation hung over any complaint. Yet they persevered because after completing that first year of service, they were granted landed immigrant status and could sponsor family members to join them in Canada.

Jean Augustine, who would become Canada's first Black female Member of Parliament and Cabinet minister, entered Canada through this scheme in 1960, working as a nanny in Toronto's Forest Hill neighbourhood before attending teachers’ college and rising through public service. Her story exemplifies the trajectory of many: women who came as domestic workers, sponsored their families, pursued further education, and became professionals, leaders, and pillars of Caribbean communities in Toronto, Montreal, and other Canadian cities.

After the Domestic Scheme officially ended in 1968, Canada's 1967 introduction of a points-based immigration system opened doors for skilled Caribbean professionals. Between 1960 and 1971, Canada accepted about 64,000 people from the Caribbean. Doctors, nurses, teachers, engineers, and other professionals arrived with their families. Yet even these skilled workers faced credential devaluation, hiring discrimination, and systemic barriers that funnelled them into positions below their qualifications.

The American Story: Caribbean, African, and the Great Migration

In the United States, Black caregiving stories encompass multiple migration waves. Black Americans have roots stretching back centuries through the horror of slavery and the Great Migration of the early-to-mid 20th century, when millions of African Americans fled the Jim Crow South for opportunities in Northern and Western cities. But the story also includes substantial Caribbean and African immigration following the liberalization of immigration law in the 1960s.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act abolished discriminatory national-origin quotas that had essentially barred non-European immigration. Combined with the expansion of Medicare and Medicaid—which created enormous demand for healthcare workers—this opened pathways for Caribbean and African nurses, doctors, and other professionals. Jamaican, Trinidadian, Barbadian, Haitian, and other Caribbean nurses filled critical gaps in American hospitals, particularly in urban centres. Like their counterparts in Britain and Canada, they often found themselves channelled into less prestigious specialties, working night shifts, and earning less than their credentials warranted.

African immigration followed similar patterns. As Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, and other nations gained independence in the 1960s and 1970s, political instability, economic challenges, and limited opportunities at home drove professionals to seek education and work abroad. Nigerian doctors trained in Lagos, Kenyan nurses educated in Nairobi, Ghanaian engineers and teachers, all came seeking opportunities their newly independent nations, often still reeling from colonial exploitation, could not yet provide. They brought skills, education, and ambition, yet frequently faced the same discrimination, credential barriers, and professional limitations as Caribbean migrants.

What united all these migrations—Windrush, the Domestic Scheme, post-1965 Caribbean and African immigration, and the Great Migration—was a fundamental truth: our parents came to fill labour shortages in post-war and post-colonial economies. They were invited, recruited, actively sought out, then systematically underpaid, discriminated against, and relegated to positions white workers refused. They did the work that built these nations' infrastructure, healthcare systems, and public services. And critically, they left their own parents behind.

The Shift That Changed Everything

When our parents migrated from Kingston to London, from Lagos to Toronto, from Port-of-Spain to New York, from Bridgetown to Birmingham, they left their parents in the villages and cities of home. Those grandparents remained embedded in extended family networks. Aunties, uncles, cousins, neighbours who were like family—these networks remained intact. When Grandma needed help, there were hands to hold her. When Papa grew forgetful, familiar faces guided him home. Our parents sent remittances, made expensive phone calls, and perhaps visited once a year if they could afford the fare. Distance was measured in thousands of miles and pounds sterling or dollars that were hard to spare. This was caregiving at a distance—financially supporting, emotionally connected, but not physically present for daily needs.

We face something entirely different. Our parents are here, aging in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. The very proximity that should be a blessing has become a double-edged sword. We are the first generation across the Black diaspora to provide hands-on, daily care to aging parents in countries that are not our ancestral homes, within systems that do not understand our cultural values, while navigating employment structures that offer scant support and facing financial pressures exponentially higher than those experienced by white caregivers.

The village that once existed to support elders, that network of blood and fictive kin, of community obligations and shared labour, does not exist here. In its place is nuclear family isolation, where one or two adult children bear the full weight of care while juggling careers that offer no flexibility, raising their own children, and trying to maintain some semblance of personal well-being.

What Makes Our Journey Different

The statistics reveal part of the story: 57% of Black family caregivers experience 'high burden' caregiving, providing an average of 30 hours of care per week—nearly a part-time job on top of their actual employment. We spend 34% of our annual income on care-related costs, compared to just 14% for white families—nearly two and a half times more. More than half of African American caregivers find themselves 'sandwiched' between caring for an older person and a younger person under 18, or caring for multiple elders simultaneously. And 64% of us work full-time while providing care, the highest rate of any racial group.

But numbers cannot capture the full reality. They cannot convey what it means to navigate a Canadian, American, or British healthcare system that questions why you want to remain in the room during your mother's examination, that doesn't understand why large extended family visits matter for healing, and that assumes families like yours don't care deeply simply because you lack the resources for private care options. These systems don't account for cultural expectations that adult children—particularly daughters—will provide the bulk of care, or the faith convictions that honouring thy father and mother is not optional but a divine mandate.

Consider the specific challenges across our diverse communities:

Caribbean families navigate healthcare providers who dismiss traditional remedies and practices as superstition, who cannot pronounce our parents' names correctly and who misinterpret cultural communication styles as non-compliance. When Mummy says she 'took some bush tea' for her pressure, the nurse rolls her eyes rather than asking what herbs she used and whether they might interact with prescribed medications.

African families deal with elders whose first languages; Yoruba, Igbo, Twi, Swahili, Amharic are spoken by precisely zero staff members in most care facilities, creating profound isolation and communication barriers. When your mother is frightened and confused and calls out in the language of her childhood, no one can comfort her.

Black American families face providers who cannot distinguish between legitimate barriers to compliance and cultural communication styles, who bring their own biases about Black families' commitment to elder care and who operate within systems that have historically and systematically discriminated against Black people seeking healthcare.

All of us, across the diaspora, face the reality that many of our parents worked jobs that were brutal on their bodies. They cleaned offices on night shifts, their knees wearing out from scrubbing floors. They lifted hospital patients without proper equipment, devastating their backs. They stood at factory lines for decades, developing arthritis and repetitive strain injuries. They drove buses through all weather, dealing with the stress and physical toll of that labour. Now they need care, but the systems providing that care were never designed with people like them in mindpeople who contributed their whole working lives but never earned enough to afford premium care options, people whose bodies bear the marks of hard physical labour, people whose cultural needs and communication styles are not understood or valued.

The Weight of Cultural Expectation

In our communities, whether Caribbean, African, or Black American, caregiving carries profound spiritual, cultural, and existential significance. It demonstrates that you were raised properly, that you understand the sacrifices made on your behalf, and that you carry forward the values of your people. In Caribbean culture, we speak of 'respecting your elders', not as an empty phrase but as a fundamental principle of how society should function. In African traditions, elder wisdom is a treasure to be protected, and caring for those who came before is how we maintain connection to our ancestors and our identity. In Black church communities across the diaspora, we learn that caring for family reflects divine love itself, that there is blessing in service, that we reap what we sow.

These are not abstract principles but lived values that have sustained Black communities through slavery, colonialism, Jim Crow, and ongoing discrimination. They are beautiful truths that bind generations together and create communities of mutual care and support. They are part of what makes us who we are, part of what we want to pass on to our own children.

Yet these same values also create tremendous pressure when the reality of caregiving exceeds what one person, or even one family, can bear. When the daughter, working full-time while raising three teenagers, must also provide 30 hours of care weekly to her mother with advancing dementia. When the son, who has already sacrificed his career advancement, loses his job entirely after missing too many days caring for his father, who needs round-the-clock supervision. When families drain their savings, sacrifice their children's education funds, mortgage their futures, because considering alternatives feels like betraying everything they were taught about family, respect, and duty.

Family Dynamics: When Love Gets Complicated

Decisions about who provides care, how it's provided, and whether professional care should be sought are rarely simple. In many Black families, these conversations brim with tension, shaped by birth order, gender expectations, geographic proximity, financial capacity, and old family dynamics that resurface with force under the stress of caregiving.

The eldest daughter is often assumed to be the primary caregiver, regardless of her other responsibilities. Never mind that she has three children, works full-time, and lives an hour away. Never mind that her younger brother is single, lives closer, and has a more flexible job. The cultural script says it falls to her. The son who moved away for better opportunities—pursuing the very success his parents encouraged—may now face judgment from siblings who stayed close to home. The child who has financial means may be expected to fund all care costs, while others provide physical labour, creating resentment on all sides. The sibling who never quite met parental expectations may see caregiving as a chance for redemption, or may be excluded from care decisions entirely, perpetuating old hurts.

Migration patterns add further complexity. The child who was left behind in Jamaica with relatives while parents established themselves in Canada may harbour both resentment and a profound sense of obligation. The adult children born in Toronto or London or New York—who absorbed different cultural norms about individualism, professional achievement, and family structure, may struggle to understand why 'just put them in a home' isn't a simple solution for everyone. Meanwhile, the parent who once provided care for their own aging parents back home, surrounded by extended family support, may resist receiving care in this foreign place, or hold expectations that their children, working full-time jobs their parents never had to navigate, raising children in environments far more demanding than the villages or small cities where they grew up, simply cannot meet.

And hovering over all of these dynamics is the question many families struggle to voice, the thought that feels like betrayal even to think: What if we genuinely cannot do this? What if trying to do this is destroying us? What if love alone isn't enough?

The Role of Faith: Source of Strength and Source of Guilt

For many Black caregivers across the diaspora, faith is inseparable from the caregiving experience. Our churches, mosques, and faith communities provide practical support—meals brought to the house, brief respite care, prayer circles that hold us up when we are falling apart, sometimes even financial assistance. They remind us that we are not alone in this struggle, that our labour is seen as sacred, that there can be purpose even in the most difficult seasons.

Yet faith can also intensify the guilt and pressure caregivers feel. Teachings about honouring parents, about suffering building character, about trusting in divine provision can make it extraordinarily difficult to admit when we are overwhelmed, when we have reached the limits of our capacity. To say 'I cannot do this anymore' may feel like a failure of faith, not simply an honest statement of human limitation. To consider professional care may feel like abandoning not just cultural expectations but divine mandate. In some faith communities, struggling is interpreted as evidence that you aren't praying hard enough, that your faith is insufficient, that seeking help outside the family represents spiritual weakness.

Some faith communities, thank God, offer tremendous understanding and practical support. They understand that faith does not require us to martyr ourselves, that God's will includes our well-being, and that seeking help is wisdom rather than weakness. But others, however well-intentioned, convey messages that trap caregivers in situations damaging to everyone involved—caregiver, care recipient, and the children watching this dynamic unfold and internalizing lessons about what family obligation demands.

The Impossible Equation: When Capacity Doesn't Equal Love

This is where we must speak truth, even when uncomfortable: an increasing number of Black families across the diaspora are coming to terms with a painful reality. They must choose professional care for their loved ones. Not because they love them less. Not because they have abandoned their culture or forgotten where they come from. Not because they have failed. But because human capacity has limits, trying to exceed those limits destroys families from within.

Consider these scenarios that play out in Black households across Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom every single day:

The daughter caring for her mother with advanced dementia while working full-time and raising three teenagers is not sleeping—maybe three, four hours a night if she's lucky. Her blood pressure is dangerously high. She has gained 40 pounds from stress eating and a lack of time for any self-care. She has missed so much work that her job is at risk. Her marriage is strained to breaking point. Her teenagers are acting out, desperately needing attention she cannot give. Her mother needs round-the-clock supervision she cannot provide, wandering at night, sometimes aggressive in her confusion and no longer able to recognize her own daughter half the time. Something will break. The only question is what, and whether that breaking will be reversible.

The son whose father requires lifting assistance that has already resulted in the son's serious back injury, who needs medication management that the son, despite his best efforts, despite the colour-coded pill boxes and the phone reminders, cannot track reliably, who wanders at night putting himself in danger. The son has lost his job. His own health is deteriorating. He snapped at his children yesterday in a way that scared them, scared him. The care needs have exceeded what one person working full-time could ever safely provide, yet the guilt of considering alternatives feels unbearable.

The family that has drained their savings, emptied their children's education funds, and pushed themselves to complete physical and emotional exhaustion—and still cannot provide the level of skilled nursing care their loved one genuinely needs. The wound care, the management of multiple chronic conditions, the physical therapy and the monitoring for medication interactions. These are not tasks love can substitute for training. These require professional expertise.

In these situations, and they are far more common than we publicly acknowledge, seeking professional care is not abandonment. It’s an honest reckoning with reality. It is understanding that love alone cannot cure dementia, that devotion alone cannot provide skilled nursing care, that cultural pride and family loyalty alone cannot create more hours in the day or more money in the bank account or more capacity in a human body and mind that are themselves breaking down under impossible demands.

Redefining What It Means to Care

We need a new understanding of what it means to honour our parents and elders—one that holds space for both cultural values and human limitations. Skilled facilities are not warehouses where we discard inconvenient family members. They are places where trained professionals can provide care that is genuinely beyond the capacity of most families. Where there is expertise in wound care, pain management and the complex medication regimens that multiple chronic conditions require. Where there are systems to ensure safety, proper nutrition and social engagement.

Choosing a care facility does not mean you stop being a caregiver. It means you transition to a different kind of care—one where you advocate fiercely for your parent's needs and dignity, where you visit regularly and remain intimately involved in care decisions, where you monitor to ensure quality care, where you bring familiar foods and music and maintain cultural connections, where you love and support without sacrificing your own health, your children's wellbeing, your livelihood, and your sanity in the process. You can still be present. You can still ensure your parents' dignity. You can still honour the cultural and religious values that shape your family. But you can do so while also understanding that professional medical care and proper supervision serve your loved one better than exhaustion, burnout, and families torn apart.

The Search for Culturally Appropriate Care

One of the greatest challenges Black families face when considering professional care is finding facilities that understand and respect our cultural values. Too many care homes operate with assumptions rooted exclusively in white, Western norms. They may not understand the importance of specific foods—the way a Jamaican elder needs rice and peas or curry goat, the way Nigerian parents long for jollof rice and egusi soup, the way soul food connects Black Americans to memory and identity. They may not understand why large extended family visits aren't disruptions, but are essential to healing and well-being. They may not grasp the significance of faith practices, the role of prayer or the need for spiritual community.

The work of finding appropriate care requires advocacy. Families must demand cultural competency, staff who respect that your mother's headwrap is not optional, who understand that different cultures have different communication styles around pain and discomfort and who can pronounce names correctly or at least make a genuine effort to learn. We must advocate for dietary options that include culturally familiar flavours. We must insist on visiting policies that accommodate large family gatherings rather than limiting them to nuclear family units.

Some communities are beginning to develop culturally specific care options, facilities designed with Caribbean or African diaspora communities explicitly in mind, where staff understand the culture, where the food is familiar and where communication styles are understood. These remain far too rare, and accessing them often requires resources many families simply do not have. This disparity itself is a form of injustice that must be addressed through policy, investment, and commitment to equity in elder care.

What Must Change: The Systems That Failed Our Parents

Individual families making impossible choices is not the solution. We need systemic change that addresses why Black families bear such disproportionate circumstances.

We need paid family leave policies that treat caregiving as legitimate work deserving protection and compensation. Currently, Black caregivers are more likely to lose jobs or face discrimination due to caregiving responsibilities, yet we have the least access to family leave policies.

We need subsidized home care services that do not bankrupt families. When we spend 34% of our income on care compared to 14% for white families, this isn't a personal failing—it's a systemic inequity shaped by generations of wage discrimination and wealth gaps.

We need tax credits and financial support that reflect the economic contribution of family caregivers—currently valued at $470 billion annually in unpaid labour. Black families provide this care at higher rates and higher intensity than any other group, yet receive the least support.

We need culturally competent care options as standard, not luxury. Facilities that understand and respect diverse backgrounds should be the norm, not exceptions accessible only to the wealthy.

We need workplace protections that prevent discrimination against caregivers, particularly for Black workers who face both racial discrimination and caregiver discrimination simultaneously.

Most importantly, we need conversations within our own communities. In our churches and mosques, our community centres, our family gatherings, where we can speak honestly about caregiving challenges without shame. Where seeking help is understood as wisdom rather than weakness. Where we can support each other in making difficult decisions. Where we can grieve the loss of the village we once had while building new forms of community support suited to our current reality.

Honouring the Fullness of Our Humanity

There is no betrayal in acknowledging human limitation. There is no shame in saying 'I need help.' There is no dishonour in understanding that caring for someone you love may require resources beyond what you alone can provide.

Our parents—whether they arrived on the Windrush, whether they came through the Domestic Scheme, whether they were part of the Great Migration or fled post-colonial instability—came to Canada, America, and Britain and built these nations. They staffed the hospitals that saved lives. They drove the buses that kept cities moving. They cleaned the offices where policy was made. They taught the children. They built the infrastructure. They endured racism, discrimination, bone-deep exhaustion, and cultural isolation so that we might have opportunities they never had. This is the generation that literally constructed the modern healthcare systems, education systems and transportation networks of these countries. They deserve to age with dignity. They deserve to receive the quality care their contributions have more than earned.

And we, their children, deserve to care for them without being destroyed in the process. We deserve systems that support rather than punish us. We deserve communities that understand rather than judge us. We deserve the freedom to make choices based on genuine capacity rather than impossible ideals rooted in a village structure that no longer exists in our diaspora reality.

The honour of caregiving is real. The love is real. The cultural values that bind us to our elders are real and precious, part of what has sustained Black people through centuries of oppression and struggle. But so too are the limits of human endurance. So too is the need for systemic support that our parents' generation never received. So too is the reality that sometimes, loving someone means understanding when they need more care than you alone can provide—and having the courage to seek that care despite the guilt, despite the cultural pressure, despite the voices telling you this makes you less than.

We can hold both truths: caregiving is sacred work, and it should not require us to sacrifice everything. This is not a contradiction. This is the fullness of our humanity—loving, limited, and deserving of support as we navigate one of life's most challenging and universal passages.

To every Black caregiver reading this—whether your parents came on the Windrush, through the Domestic Scheme, during the Great Migration, or from Lagos or Accra or Nairobi seeking a better life: Your love is evident in your exhaustion. Your honour is proven by your presence, day after day, even when you have nothing left to give. Your culture is alive in your commitment. And your humanity—with all its beautiful limitations—is worthy of protection, support, and grace.

Sources: National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP (2015), Caregiving in the U.S.; CDC, Caregiving for Family and Friends—A Public Health Issue (2020); Bureau of Labor Statistics (2021-2022); HR Life & Work Connections, Black History Month: Honoring Generations of Family Caregivers (2025); The National Archives, Empire Windrush: Caribbean Migration (2024); Royal Museums Greenwich, History of the Windrush; Heritage Toronto, West Indian Domestic Scheme; Parks Canada, West Indian Domestic Scheme National Historic Event; The Canadian Encyclopedia, West Indian Domestic Scheme and Caribbean Canadians; PMC, Extended Family Support Networks of Caribbean Black Adults in the United States (2017); PMC, Attitudes and support needs of Black Caribbean, south Asian and White British carers of people with dementia in the UK (2008); PMC, Caregiving Across International Borders: Transnational Carer-Employees Systematic Review (2018); People's History of the NHS, The Windrush Generation and the NHS: By the Numbers (2019); History & Policy, Immigration and the National Health Service (2025).